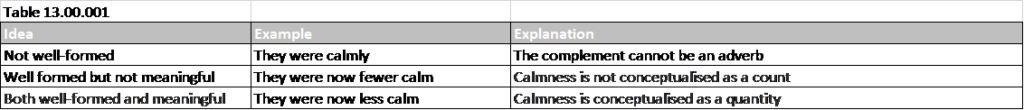

What is the relationship between syntax and semantics? Syntax is a matter of form. A syntactically correct statement is one that is well-formed. Semantics on the other hand is a matter of the validity of the content. Well-formed syntax is usually necessary but not sufficient for meaning.

The first example here isn’t a well-formed statement because a complement must be a noun term or an adjective term and calmly is an adverb. The second example is well-formed because the complement is an adjective and an adjective can be qualified by an adverb. However, it is not meaningful because calm like all adjectives, is conceptualised as an amount and the adverb fewer applies to things that can be counted. The correctly formed and meaningful statement is therefore the third, where the complement is qualified by an adverb applicable to amounts.

This argument implies that what is semantically valid is a subset of what it syntactically well-formed. That is, the population of semantically valid statements is contained within the population of syntactically correct statements.

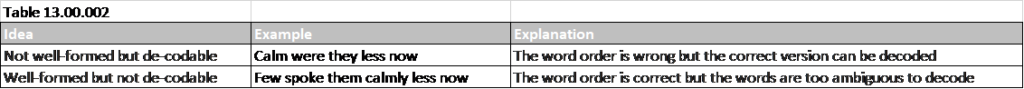

However, it is necessary to introduce a couple of caveats. The first is the degree to which a statement is de-codable.

We are very good at decoding seemingly obscure messages and these become challenges in anagrams and crosswords. We can often still pick the meaning out of distorted and scrambled statements, words and letters in the wrong order, words and letters missing, substitutions and so on. Meaning can found in a mashed-up and elided version of a statement.

You could argue that therefore semantics and syntax would be overlapping in a Venn diagram rather than semantics being contained within syntax but I would argue that in these cases the meaning of the syntactically incorrect version is derived from an intuitive grasp of the syntactically correct version.

Although the first statement is meaningful it is only so by virtue of the fact that it can be decoded. Calm as an adjective cannot be a subject and they as a subject pronoun cannot be a complement. However, these elements can be re-ordered into a version that is unambiguously correct so we can therefore be confident that the word order here has been scrambled.

The second example, though well-formed, isn’t de-codable, because there is no other correct syntax for this set of words that yields a meaningful statement.

The second caveat is that creative an evocative writing may break syntax deliberately. The grammar of the English language is sufficiently flexible that there is rarely a need for anyone writing deliberatively, the style of language we use in critical and forensic thinking, in journalism, business, politics, science, history and philosophy, to break the rules for a well-formed statement. However, in creative and evocative writing and speech, in fiction, poetry, theatre and film, writers often push language into a form it doesn’t normally take, stretching through rhetorical devices the limits of syntax and morphology and, when necessary, breaking the rules of well-formedness.

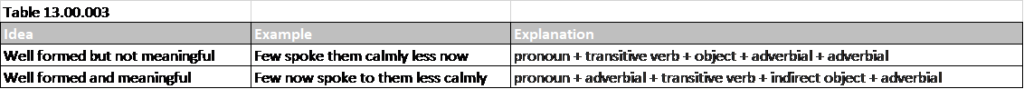

So, what makes a semantically meaningful sentence. What distinguishes a meaningful well-formed statement from a meaningless one? One reason is unresolvable ambiguity. For example, consider the two statements in the next table.

Firstly, it’s not clear in the first sentence whether them is a direct or an indirect object. Does it refer to the words spoken or the party they were directed towards. Both would be valid. Secondly, it’s ambiguous what the adverb now qualifies. Does it mean that the few now spoke as opposed to writing, or does it mean that they spoke now rather than at some other time, or perhaps that they spoke less calmly now than earlier.

The second statement includes two minor revisions which resolve these ambiguities. It’s still not a elegant statement, but it is well-formed and meaningful.

Secondly, a statement may not be meaningful because it expresses an incoherent idea. Noam Chomsky’s well-known example, Colorless green ideas sleep furiously, illustrates this. The statement is well-formed but lacks coherent meaning. Something that is the colour green cannot also lack colour, and colour is not a valid attribute of an idea. Similarly, ideas can form and travel and be adapted but they cannot sleep, in the same way that I can put my laptop into a sleep state but it isn’t sleeping or asleep because sleeping is something you do, not something that is done to you. Furthermore, we can sleep peacefully or our sleep may be troubled but sleep is a not an activity that can be engaged in furiously.

There is effectively a conceptual schema that lies behind a meaningful statement. The words in the statement refer to the concepts in this model. The model defines how conceptual ideas are related to each other and what attributes and values can be applied to them. We understand this conceptual schema intuitively. We know that ideas don’t sleep and don’t have a colour, and we know that furiously is not a value that can describe how we are sleeping. This doesn’t mean they cannot be meaningful because they can but the statement is meaningless because they aren’t. When we learn a language, we intuitively pick up the underlying conceptual schema in which concepts are modeled.